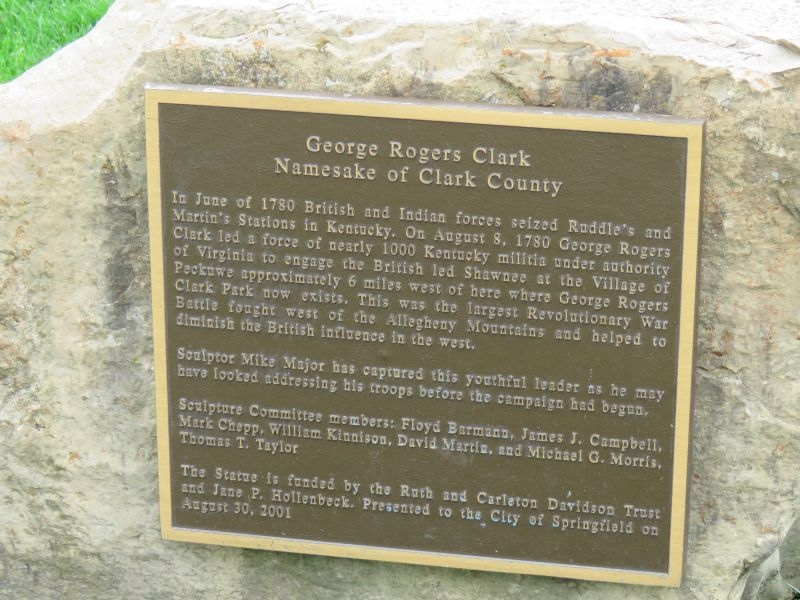

Clark County is in west-central Ohio. Created in 1818, it was named after Brigadier General George Rogers Clark, a hero of the American Revolution, who died that very year.

George Rogers Clark (November 19, 1752 – February 13, 1818) was an American military officer and surveyor from Virginia who became the highest-ranking Patriot military officer on the northwestern frontier during the Revolutionary War. He served as leader of the Virginia militia in Kentucky (then part of Virginia) throughout much of the war. He is best known for his captures of Kaskaskia in 1778 and Vincennes in 1779 during the Illinois campaign, which greatly weakened British influence in the Northwest Territory (then part of the British Province of Quebec) and earned Clark the nickname of “Conqueror of the Old Northwest.” The British ceded the entire Northwest Territory to the United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris.

Clark’s major military achievements occurred before his thirtieth birthday. Afterward, he led militia forces in the opening engagements of the Northwest Indian War, but was accused of being drunk on duty. He was disgraced and forced to resign, despite his demand for a formal investigation into the accusations. Clark left Kentucky to live in the Indiana Territory but was never fully reimbursed by the Virginian government for his wartime expenditures. During the final decades of his life, he worked to evade creditors and suffered living in increasing poverty and obscurity. He was involved in two failed attempts to open the Spanish-controlled Mississippi River to American traffic. Following a stroke and the amputation of his right leg, he became disabled. Clark was aided in his final years by family members, including his younger brother William, one of the leaders of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He died of a stroke on February 13, 1818.

Clark is most famous for leading the Illinois Campaign during the American Revolution, where he led less than 200 militiamen hundreds of miles through the wilderness and captured Kaskaskia and Fort Vincennes by surprise from the British. He is often credited for nearly doubling the size of the original 13 Colonies by taking this land, in what became the Old Northwest Territory.

The march on Fort Vincennes- 180 miles long, which took place in winter, over flooded ground- is legendary. It has been reproduced by artists over the years. Here’s a mural in the George Rogers Clark National Memorial at Vincennes, Indiana-

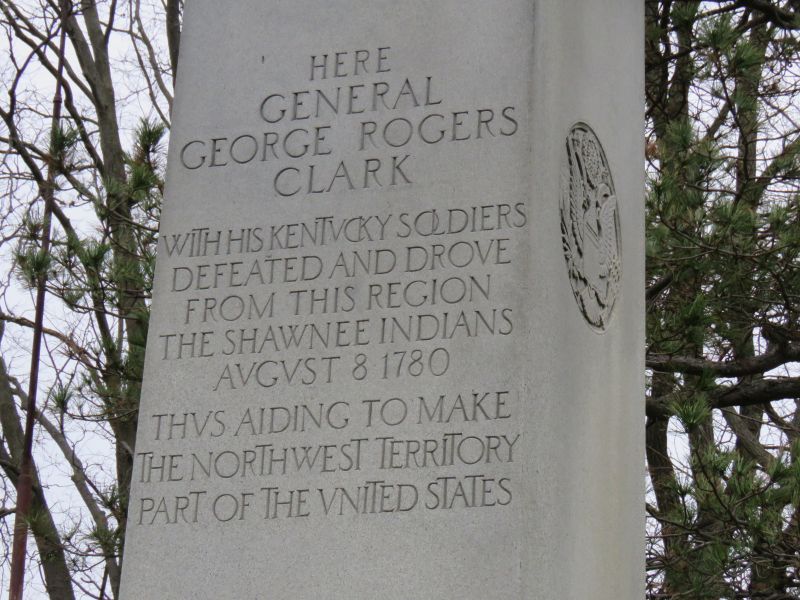

Clark opened up the Northwest Territory to the United States. But another action of his is more relevant to Clark County, Ohio- he led American militiamen to victory in the greatest battle of the American Revolution west of the Allegheny Mountains, in what ended up being Clark County.

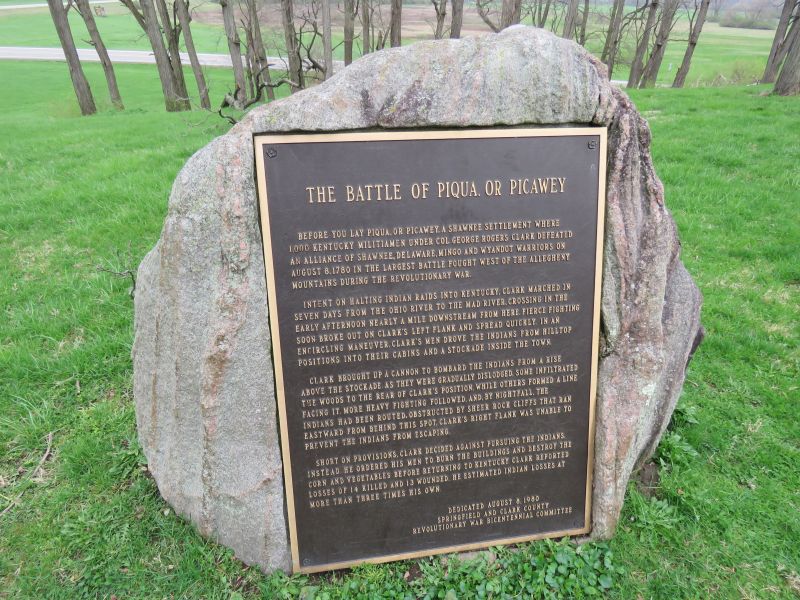

The Battle of Piqua was in response to British raids into Kentucky Territory- then a part of Virginia. Clark led nearly 1,000 militiamen to attack the Shawnee village of Piqua- there are various spellings- where the Shawnees under Chief Black Hoof had retreated from their capital of Chalawgatha (near present-day Chillicothe). The battle was fierce, and Clark lost some men but eventually prevailed and burned the town, crops and stockade there. The Shawnee retreated north and settled along the Great Miami River at present-day Piqua Ohio. Native American villages moved every so often, so the same village may have been located in multiple locations.

This battle ended the British and Shawnee threat to Kentucky, boosting American morale, and foreshadowed the Northwest Indian War that took place in the 1790s. The battlefield was turned into George Rogers Clark Park– one of several in what was once the Old Northwest Territory- to commemorate the man and his battles, and also the birthplace of the great Shawnee warrior Tecumseh (in the general area). Tecumseh was about 12 years old at the time and remembered the chaos of the battle.

A George Rogers Clark memorial statue is on the park grounds.

Many tributes have been made to Clark, one of them includes the naming of Clark County Ohio in his honor and the George Rodgers Clark Park that commemorates him defeating the Shawnees at the site of the Battle of Piqua. In the park, stands a statue of him by Charles Keck, carved from Victoria White Granite by the George Dodds Granite Company. The full-size sculpting of Clark stands atop a Victoria White pedestal is among one of the greatest tributes to Clark. It is just one of many civic memorials created by the George Dodds Granite Company that still stand today as a testament to the craftsmanship that Dodds was known for then and still today.

This park is a nice destination for nature lovers as well.

The Daniel Hertzler House stands on the park grounds.

The Daniel Hertzler House, near Springfield, Ohio, was built in c. 1854. It is a brick house of Pennsylvania “Bank Style” architecture, larger and more complex than other historic structures in Clark County, Ohio. It was listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

Hertzler became wealthy in the milling and distilling business in Mad River Township, selling that in 1853; and then entering into businesses in Springfield, including a Clark County Bank. He had nearly completed construction on a new milling business, when he was murdered in his home on the morning of October 10, 1867.

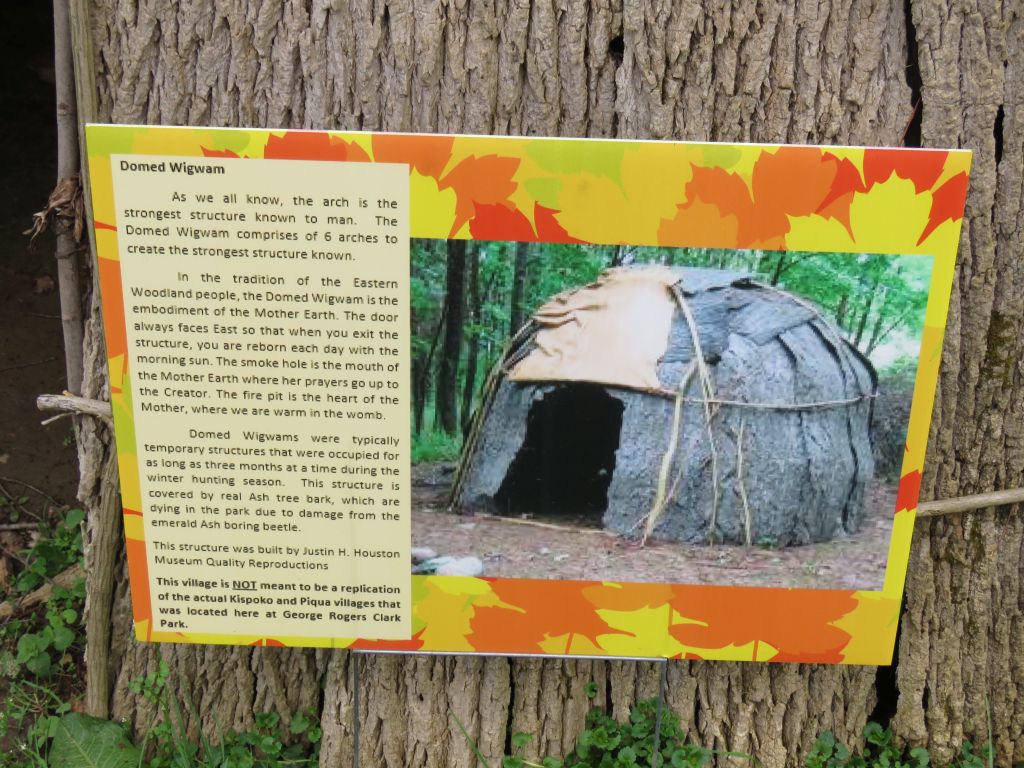

Within the park is a recreated Native American village, showing various styles of dwellings of the eastern woodlands tribes.

Every Labor Day weekend, George Rogers Clark Park is host to The Fair at New Boston, a visit back in time to the years 1780-1810, the era that Ohio became a state. The Battle of Piqua is often featured. Re-enactors of the time abound, and they stay in character as if it was the year 1800 or so. The George Rogers Clark Heritage Association puts this event on every year. The Fair, which started in 1982, is well-attended. I was there- with my camera- in both 2022 and 2023.

You can speak with re-enactors to learn about colonial times in the Ohio frontier. Ohio became a state in 1803; the Northwest Indian War took place there in the 1790’s, after which the floodgates to American settlement opened.

Re-enactors are dedicated to history, donating their time and money to these events. Accurate clothing and equipment of the era is a necessity.

This re-enactor did Native American crafting. He said birch bark was a sought-after material to make items, due to its flexibility and oiliness.

The Great Elizabeth was one of the re-enactors, showing how actors often performed Shakespeare in the era.

A highlight of her show was to pick would-be actors in the audience, who would orate Shakespearian insults.

The First Mad River Light Artillery shows off their replica British Light 6-Pounder (and a smaller piece). The gunner is shielding the powder touchhole with his hat to prevent a spark setting off the cannon before it was ready to fire. Needless to say, it makes a very satisfying boom when fired.

This re-enactor highlighted the importance of oxen in the western migration of settlers across America. The ox was the 19th-century workhorse of America, not the horse- 700,000 of them went west, versus 7,000 horses. They were less expensive, and could forage grass to eat, avoiding expensive grain feed that horses needed. Their drawback was that they were slow, moving 3 miles per hour. They could plow a square acre (43,000 square feet) in one day. Oxen pulled settlers’ wagons westward- the settlers would walk alongside the wagons so more cargo would fit in them.

This is a Red Devon ox- the breed came to America in 1623. There are only 2,000 of them left now. All cattle had horns until relatively recently- they started to be de-horned in the 19th century. Horn was the plastic of its day, used for making powder horns, spoons and other implements. Native Americans wanted horses, not cattle- settlers did not eat horses due to the Biblical injunction against eating split-hooved creatures. It is hard to imagine the numbers of oxen in 19th-century America- in Indiana in 1854 there were 450,000 of them.

This re-enactor portrayed Black Hoof, the great Shawnee chief who eventually made peace with the Americans- he saw the future accurately, that there were too many settlers to fight. He and Tecumseh were bitter rivals. He spoke (out of character) of visiting Black Hoof’s grave in St. Johns, Ohio, his voice breaking with emotion. He inspired me to visit the grave- next year’s post will be about the Shawnee.

He talked of Shawnee life at the time. The Shawnee valued white trade goods and silver, which they mostly obtained from traders and wore as jewelry. There are persistent legends of hidden Shawnee silver hordes. Eastern Native Americans walked most places as there were few roads in the vast woodlands. Horses were too valuable to risk in warfare.

The Indiana Territory Mounted Rangers re-creators gave a talk and demonstration. They were scouts (called ‘spies’ at the time) that would fight hostiles or bandits, typically being out in the wilderness for a month at a time with all their possessions on their horse. Pay was low, $5 a month plus $5 per confirmed kill. They wore black and red hunting frocks as their uniform- it was difficult to tell friend from foe due to whites and Native Americans interbreeding.

They gave a demonstration of mounted combat. A fight may start off with firing a pistol, then using it as a club before drawing your saber. Saber moves were backslash, foreslash, and back saber (protecting your back). ‘Always keep moving’ was a good strategy in battle, you kept your initiative that way. Horses would fight too- biting and bowling over enemies.

Half of the horses the re-enactors rode were rescue horses.

One of the National Road mile-markers that can be found along present-day Route 40. These came later in Ohio history, in the 1830s. I did a post on the National Road Museum 6 years ago.

A highlight of the Fair is a battle re-enactment. The battle varies from year to year, sometimes the Battle of Piqua (depending on the number of Native American warrior re-enactors), sometimes the Whiskey Rebellion era, or fights with bandits.

There is always an historical interpreter to talk about the battle and take questions from the audience.

And a good time was had by all!

See you next year, friends.

If you are interested in the fascinating life of George Rogers Clark, I recommend the historical novel Long Knife by James Alexander Thom.

A very worthwhile read.

I like the idea of reading out Shakespearean insults. That is not something you see at every re-enactment.

LikeLike

It was very humorous, tootlepedal- people really hammed it up! It was a memorable part of the day.

LikeLike

I can imagine.

LikeLike