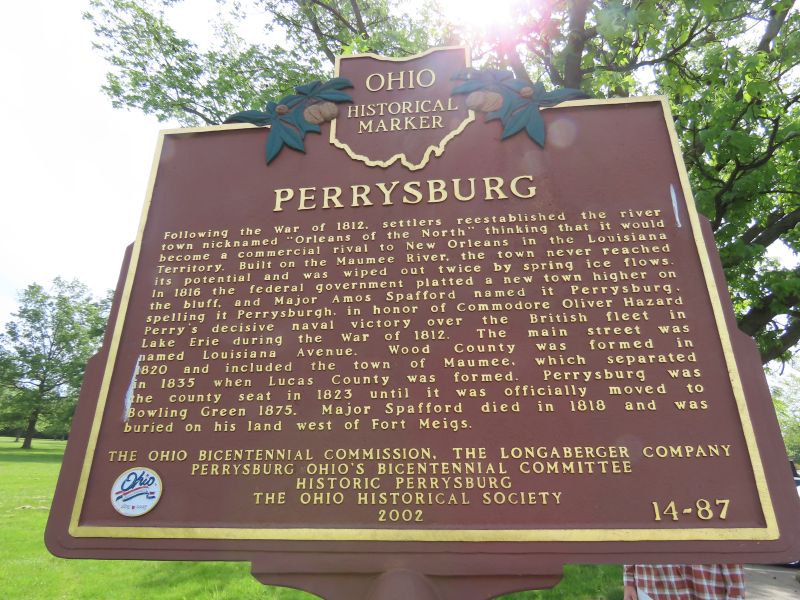

Fort Meigs is quite pleasing for the Ohio history buff. Located in Perrysburg, it is a museum and a re-created fort that saw military action in the War of 1812. Over Memorial Day weekend, reenactors gather there to share their love of history with the public.

A buddy and I drove up north earlier this year to see this historic spectacle. We stayed off of the freeway as much as we could to enjoy an Ohio travelogue experience.

We arrived not long after the weekend event opened on Saturday. There was a good crowd on hand.

As usual, I picked up a souvenir shirt. The gal who designed the shirt was on hand, which was cool. It was made here in the area. Buying local is always fun.

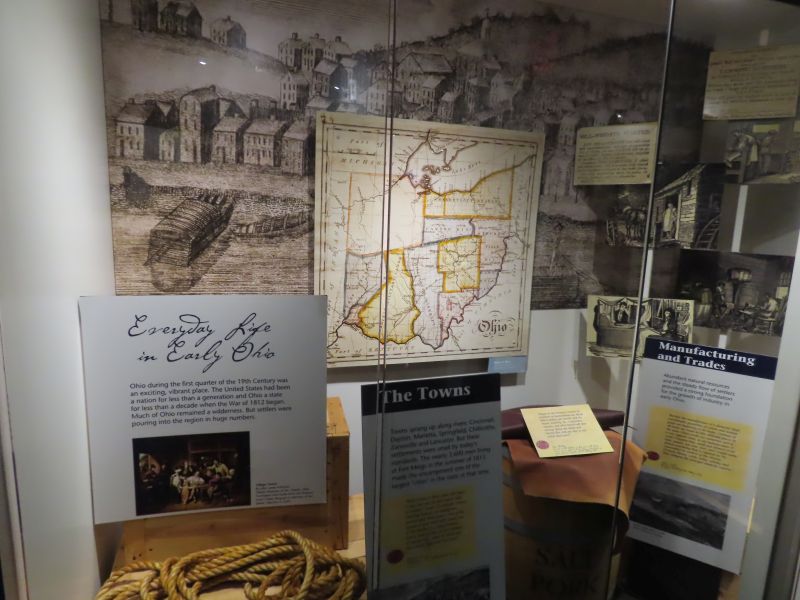

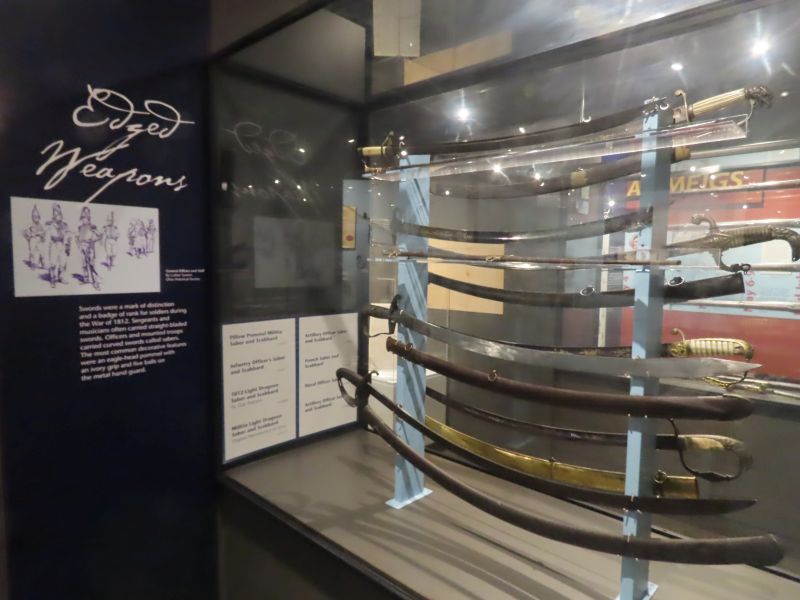

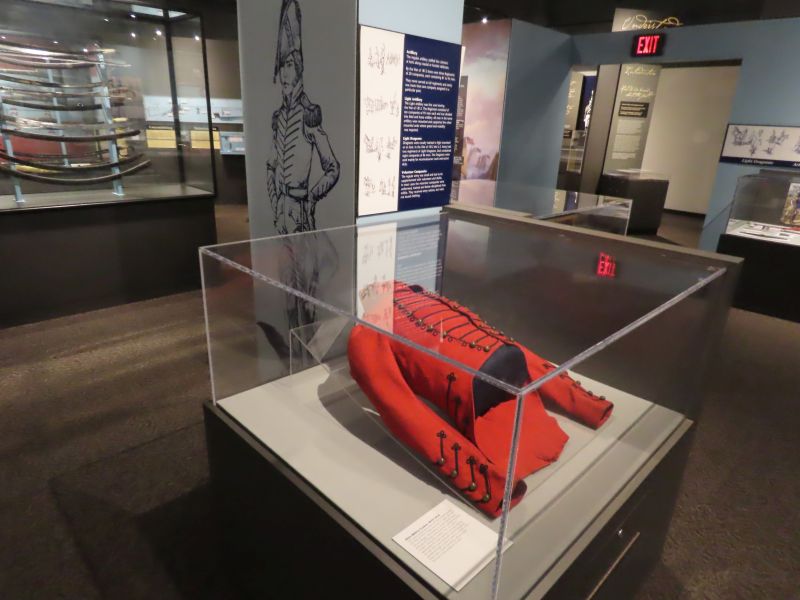

The museum was informative and well-stocked with artifacts.

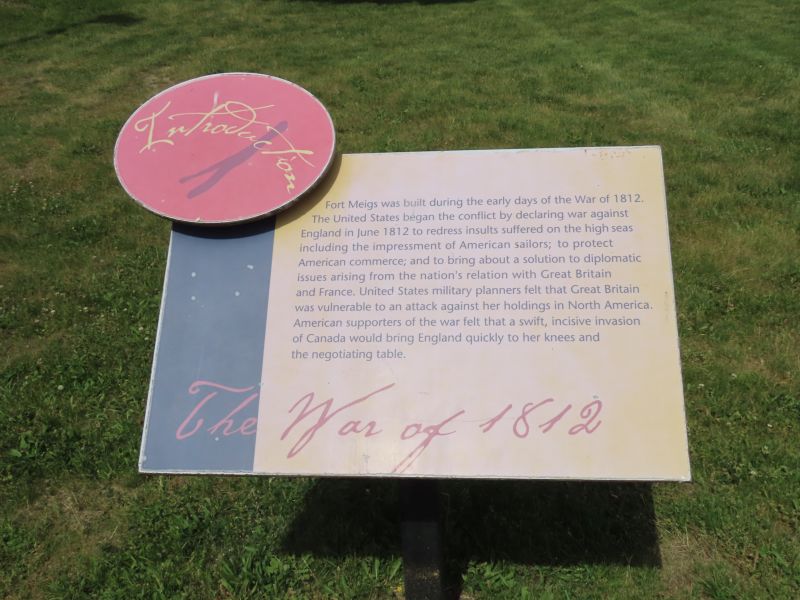

Fort Meigs, named after then Governor of Ohio, Return Jonathan Meigs, Jr., was first built as a reaction to British attacks on American forts in the Northwest Territory during the War of 1812. It was built in what is now Perrysburg, Ohio, on a bluff overlooking the Maumee River rapids. Ground was broken on February 2, 1813 under the orders of General William Henry Harrison, who wanted to fortify the region. Throughout the next three months professional soldiers and militiamen alike persevered through cold winter weather and mud that would at times be knee-deep. Despite horrid weather and disease in the camp, the American army was able to complete Fort Meigs by the end of April, 1813, just in time for a British attack.

In late April 1813 the British, under command of General Henry Proctor, arrived to begin a siege of Fort Meigs. Traveling down from Fort Malden, Upper Canada, they made camp in the ruins of old Fort Miamis on the north side of the Maumee River. On the morning of May 1, British artillery opened fire on the American installation. The bombardment carried on for five days, but the Americans within the fort held on until reinforcements, in the form of 1,200 Kentucky militia, arrived along the Maumee. These reinforcements fought several engagements on both sides of the river. Wednesday, May 5, 1813 marked the bloodiest day of the siege. During the course of the fighting, nearly 600 men were lost to a combined force of British regulars, Canadian militia, and American Indian warriors. Despite this major loss to the Americans however, many American Indians lost interest in the siege. After a few more days the British and their Native allies were forced to withdraw, leaving the Americans with a victory. The British and their allies would not return to Fort Meigs again for close to two months.

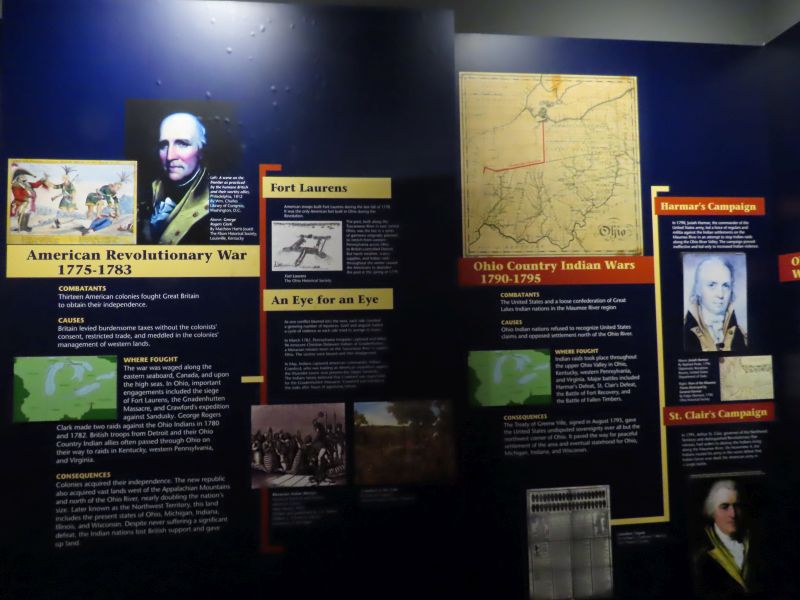

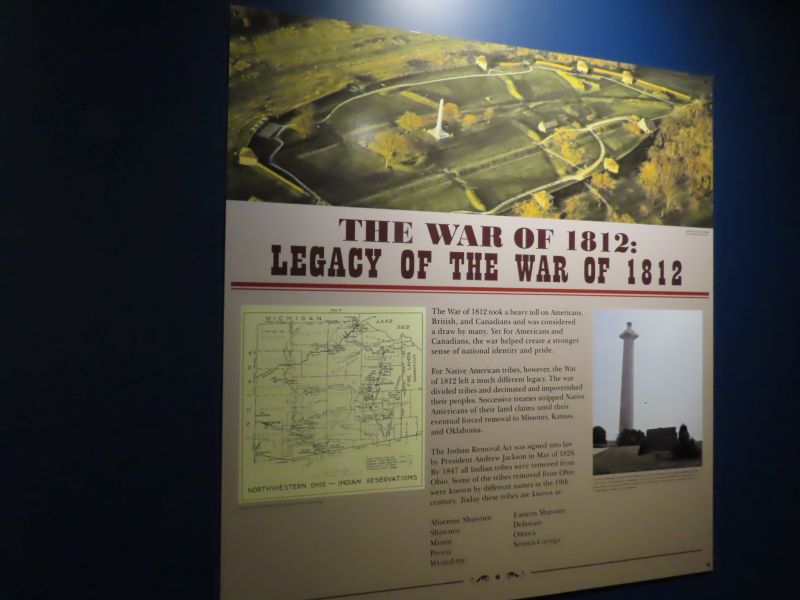

The War of 1812 was a coming-of-age experience for the young United States. In some ways it was a continuation of the Revolutionary War. There were many defeats- the loss of Fort Detroit, the unsuccessful invasion of Canada and the burning of Washington DC to name some, but a few crucial victories, such as Perry’s victory at the Battle of Lake Erie, the Battle of the Thames where Native American leader Tecumseh was killed, and Jackson’s winning of the Battle of New Orleans. The British were preoccupied fighting Napoleon in Europe.

A guided tour of the re-created fort- plus demonstrations of artillery and infantry tactics, and exhibits of life at the time shared the love of history with the general public.

The fort was a substantial size- at the time it was the largest wooden-walled fortification in North America. Note the earthen slope that was built against the fort’s wooden walls- this substantially reinforced the fort against artillery bombardment. Blockhouses (as seen in the photo above) were used for defense, not living quarters. The troops lived in tents. Winter weather was harsh (a sentry froze to death on his 2-hour guard shift).

The fort was rebuilt on the exact site of the original fort in the 1960s, and the museum opened there in 1974. Many of the artifacts found on the site are in the museum. It takes up 10 acres.

The reenactors stayed in tents just like the troops they were portraying. Note the 15 stars on the American flag, even though at the time there were more states than that (it was considered to be too cluttering to add more at the time- that changed by 1820).

It was fairly hot weather, worth finding some shade.

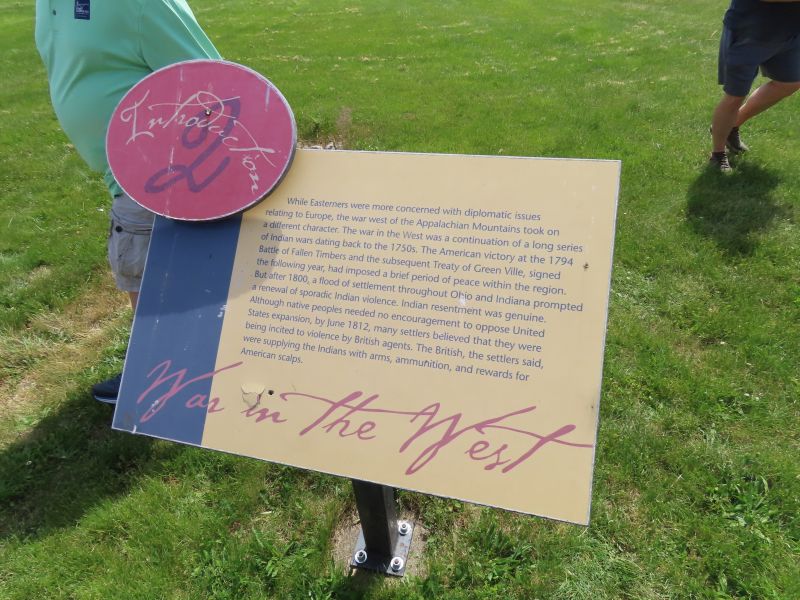

In the early 19th century, the American West was the Old Northwest Territory, consisting of the area of modern Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota. City slickers lived along the east coast.

This blockhouse was a museum in its own right.

In 1908 a memorial obelisk was raised to commemorate the site and the battles fought there.

An artillery battery was located at the fort. Reenactors demonstrated how cannons were fired and answered questions the public had.

There were several steps in firing a cannon. Here a cannonball handler hands the ball off to a carrier that stores the ball in a satchel (to keep a spark from igniting the round) before walking it to the cannon. Note that artillerymen wore blue coats with red piping.

Cleaning the barrel between shots was vital- a live spark could set off a round prematurely.

Firing the cannon was of course a loud event! A standard 6-pounder cannon of the time (firing a 6-pound shell) could fire a mile or two with varying accuracy. Napoleon came up with the brilliantly diabolical idea of firing cannonballs along the ground so that they would swiftly roll through infantry formations. It was a terrifying tactic.

A rifle company drill showed how light infantry fought and maneuvered. The Regiment of Riflemen was created before the war, because rifles- far more accurate than muskets- were seen as valuable weapons of war. Americans in the West often used rifles for hunting as well as defense. Their distinctive uniforms were of green wool with yellow trim. This was good for morale, looking different than standard troops.

An officer- a Captain by his insignia- shared all sorts of interesting information with the public. He asked us, ‘who do you think riflemen targeted to shoot?’, and I waggishly answered, ‘Captains!’

Riflemen indeed looked for officers, NCOs (Sargents etc.) and musicians. Why musicians? Because they were vital to communicating between officers and their troops by the tunes they played (advance, retreat, move left or right, fire, and so on). Dense smoke on the battlefield often obscured visual signs. This was one reason the British wore bright red, so they could be identified. Certain units who wore brown or gray were fired upon by their own troops during the war, due to smoke and confusion.

Light infantry were used for scouting, screening the main body of infantry, and harassing the enemy. They would fight in open formation in 2-man teams- one man would fire and reload while the other man guarded him.

Here the riflemen advance and fire.

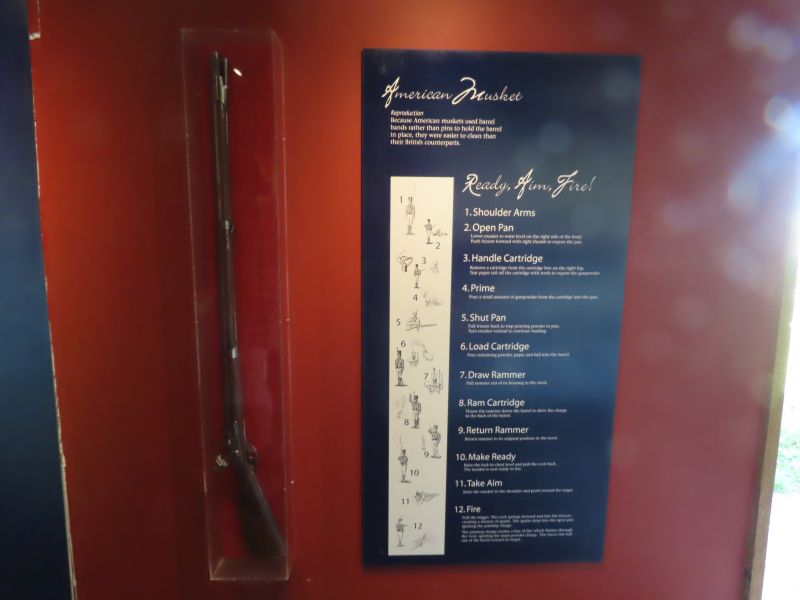

There were several steps in reloading a rifle or musket. Rifles were smaller than muskets but heavier due to barrel weight. The rifle ball fit into the barrel tighter than a musket ball. Rifles fired at a slower rate of fire- perhaps once a minute versus a musket firing at 3-4 times a minute. But they were more accurate and had greater range.

There was resistance to using rifles. Many officers saw masses of men with muskets as creating their own accuracy- if you fired a lot of lead downrange, you hit things. But at 400 yards distance, muskets had a 40-yard spread (that’s pretty lousy accuracy).

The gentleman yelling commands in the foreground is a Sargent, a non-commissioned officer that mingled with his men and led them in their formations. Note he also carries a tomahawk and knife, common among light infantry.

The timeless attitude of an NCO like this Sargent would be for him to say, ‘No, I’m not an officer, I work for a living’.

Notice the men not wearing the green uniform- they were militia, not regular soldiers. Militia was important in this time when standing armies in America were small and viewed with suspicion by the public (they were often seen as instruments of tyranny). Militia were volunteer armed civilians. They varied in effectiveness. Some left when their 90 day enlistments were up, right on the eve of a battle. One must remember that these men had to grow and tend crops at home and they would worry about their family’s safety. Militia and regular troops often didn’t get along too well.

This is a skirmish line performing harassment fire at the enemy. Unfortunately, these riflemen were issued the 1803 Harpers Ferry Rifle, which was of abysmal quality. The army actually sent the rifles back to their makers to get them repaired.

A superb demonstration!

There was a reenactment of a prisoner exchange which turned into a brief firefight when things went wrong.

These ladies in the camp demonstrated how wool was carded and spun into yarn and cloth. Before the Industrial Revolution, such activity was done in many a home. The food looked good too!

The final event for the day was a reenactment of one of the battles fought at the First Siege of Fort Meigs. An announcer shared a wealth of knowledge with the public.

Notice the American regular troops have dark blue coats but their musicians have red coats (for higher visibility).

The British wear their traditional redcoats. The man kneeling in the foreground is a Pioneer, a combat engineer at the time. They would create or dismantle obstacles.

Note that the British Sargent has a polearm, not a musket (his job was to tell his men what to do, and it’s hard to do that while going through several reloading steps with a musket).

American Riflemen cover the flank of American troops. Note a militia unit in the background.

The American regulars move up.

Militia fire at the British.

The British return fire. Great Britain was the military superpower of the day (along with Napoleon’s France). They used the largest-caliber ammunition of the war for their muskets, .75 caliber. Americans used .50-.60 caliber rounds, which meant the British could use captured American ammo but the Americans couldn’t use Brit rounds.

You will notice the occasional out-of-uniform person fighting for the British- these were Canadian militia. French woods-runners had good relations with Native Americans, who mostly fought for the British.

British bagpipers would be behind British troops because they were a prime target for American sharpshooters.

At the conclusion of the battle, American musicians played a memorial tune for all of those that fell in the War of 1812.

All doffed their hats with respect.

Reenactors spend a lot of time and money on their hobby and love sharing history with the public. They are as accurate as they can be with their gear.

All the reenactors returned to the fort- to prepare for tomorrow’s events.

We returned home with a lot of photos, memories and historical knowledge. It was a great time!

A splendid event, well illustrated. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thanks for reading and commenting, tootlepedal!

LikeLike